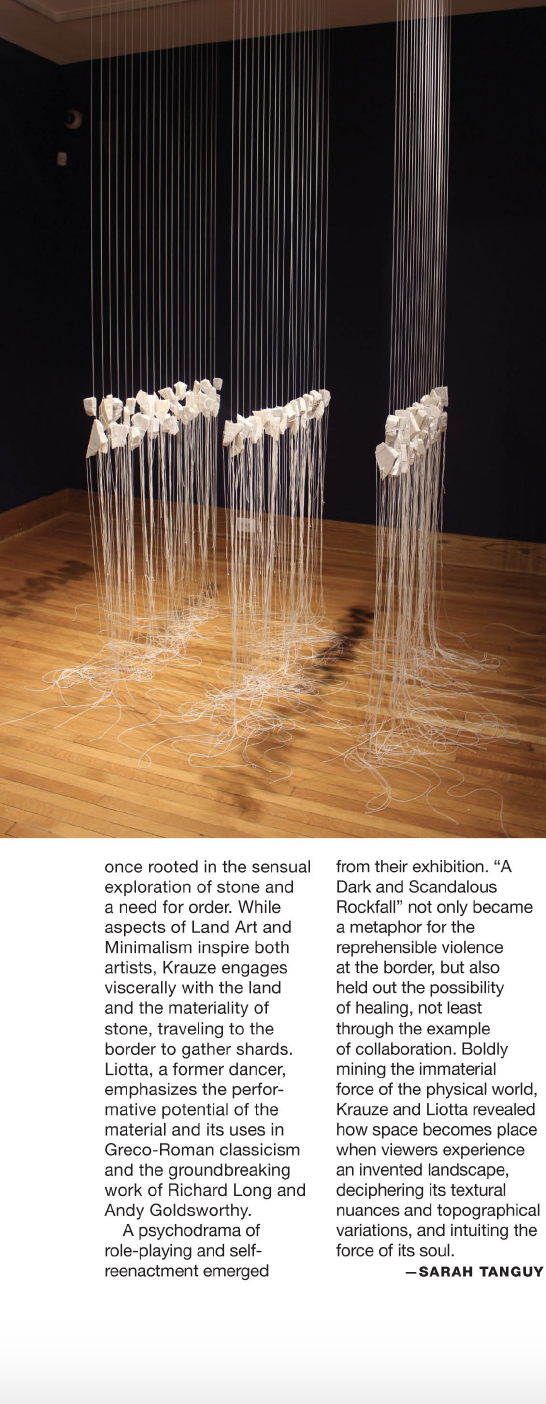

“Katzen Pegaea” (2024-2025) by Barbara Liotta makes the most of the space. Her sculptural installation hugs one of the corners of the courtyard. For the piece, the artist suspended chunks of marble, granite and quartz using rope line to form rows of rocks that float in space. This sculpture was made as a kind of spatial line drawing with this site in mind, and it shows. “Katzen Pegaea” is one of the few pieces that afford the viewer the opportunity to stand back and take them in on their own terms.

Is Barbara Liotta’s art “AirArt”, where stone LandArt is hung on threads? (Stone Ideas)

Read the full article here.

In LandArt stone is often used to create circles or lines in the landscape. Research on Barbara Liotta’s hanging stones gave us the idea that her art could perhaps be called “AirArt”, where LandArt arrangements are rotated by 90 degrees and hung by threads? She liked the idea.

Without a doubt, the American artist Barbara Liotta makes quite extraordinary art. At first glance, she simply hung small stones on threads, and inside you can see a kind of airy curtain.

In some works, the threads underneath the stones go even further and get lost in a tangled ball on the ground.

But if you take a closer look at the works of art, in addition to the materials stone, thread and suspension, two other media are added: firstly, the wind, which can set the whole arrangement in slight motion, and secondly, the shadow, which draws a copy of the work of art on a wall, for example. If the light source also moves, then even without wind, for example indoors, there is suddenly movement in the work of art.

Barbara Liotta clarifies that this is the case in all these works. Only apparently rigid, there are vibrations in the long threads even without wind, for instance when vibrations such as footfall sound are absorbed from the ceiling of an interior. She draws the comparison of her installation with a musical instrument: “It breathes, as in the vibrato of a stringed instrument.”

This is probably where the influence of her education is reflected: Barbara Liotta studied fine art and dance at Sarah Lawrence College in Cleveland, USA, where she was “born to art-conscious parents”, as her webpage states.

She outlines the guiding principle of her art as follows: “The work should be as clear as chamber music and as graceful as a dance.”

Note that she also uses a sledgehammer to bring stones in the desired size. This, in turn, is reflected in her works of art and gives them tension and life, as she puts it: “All of the work floats between the lyrical and the formal, the powerful and the melodious, the violent and the beautiful.”

Let’s take a closer look at what she means: the formal is the strict lines of the threads, the lyrical and melodic are the movements or vibrations in which the threads can get caught, the powerful and violent is the energy of the hammer stored in the stones.

Her works can be seen not only in public parks or museums, but also in private homes. There they are a truly extraordinary type of interior design. She then develops the respective forms together with the client with whom she selects the appropriate stones.

She gets them from Fernando’s Marble, a stonemason in the town of Rockville, Maryland in proximity. His family is of Portuguese descent, and she shares the love of the material with the owner. He sometimes points out special varieties, and is incredibly supportive, tirelessly collecting fragments which might suit her needs, she writes.

The threads are made of a special polyester in white, black or grey. The fabric must be extraordinarily strong, must not stretch under the weight of the stones and must not tend to get tangled.

Barbara Liotta has also made sculptural works. She also draws bas relief.

‘This Is What We Train For’ (The Atlantic)

Read the Full article here.

By Deborah Fallows

I talked with Barbara Liotta, who is an artist in Washington, DC and for the record, a longtime friend. For decades now, she and I have talked about everything: children, husbands, families, her art, my writing, travel, swimming, books, and lots of other things. I’ve traipsed around rock quarries with her to source stones for her sculptures, watched her suspend a 57-foot net panel over the side of an 11-story building, and celebrated her openings. She has visited us on our faraway journeys, flown in our little plane, gone to my author events and had parties for them. We prop each other up. So naturally, I turned to Barbara to help me see her artist’s sense of life during this time.

Barbara has a studio behind her house; it used to be a garage, with a concrete floor and high enough ceiling to hang her work. At the beginning, she told me, the lockdown made her feel like a character in a 1940s British movie. We should “buck up and take care of each other and confront this thing by being good community members,” she said. While most of us were cleaning out attics or basements, she was sorting and arranging her enormous collection of formidable, heavy shards, chunks, and slabs. Serendipitously, she came across what she described as “beautiful, gold, sun-drenched granites” and she created a series of warm sun pieces to will in a different mood.

Weeks passed, and as the pandemic with its tragic and awful state came to dominate everything, her work reflected the change. She told me. “As an artist, I can’t not address it, but the immensity of the shift requires that I let it sink in and allow my vision to mature.” The result? “I’ve been drawing and proposing a very dark, dark piece of exploded columns and shattered rock.”

Like for the rest of us, who seek some lightness or humor anywhere these days, one bright moment came on a video call with her son, an emergency room doctor in San Diego, and his new wife, as she was directing them how to install a small hanging sculpture she had shipped them. “A little farther back, off to the right, now left a bit,” she narrated the smartphone-enabled installation process. I saw this as a simple, lighthearted moment. Barbara saw an interpretation: “Art means civilization means hope,” she wrote me, “like an equation.”

Like many other artists and many of the rest of us, her work has been sidelined from the public. An exhibit at the Gallery at MASS MoCA hangs inside for no one to see it. A symposium was canceled. Future events are falling by the wayside. While many artists have shifted online—musicians, singers, actors, performing artists—Barbara says that option doesn’t work for her. Her art is three-dimensional, and being present helps experience it. “The trouble with my work now is that it needs a venue,” she concluded, with the pain of the sculptor’s version of If a tree falls in the forest …. “It is my work, but my work is not going anywhere. It doesn’t count if no one sees it.”

Perla Krauze & Barbara Liotta (Sculpture Magazine)

Home & Design: Suspended in Time

“Barbara Liotta’s work captures the raw energy of shattered stone”

Read the Full article here.

By Donna Cedar-Southworth

Barbara Liotta’s sculptures transfix and mesmerize viewers in a visceral way. Made with shards of stone and cord hung from a visible piece of hardware, her contemplative creations inhabit and animate the spaces in which they live.

Liotta draws parallels between her work and the art of ballet. “A ballet teacher once told me, ‘When you do a leap, you go up in the air, do what you’re going to do with your feet, then pause and stretch for a moment. And then you come down,’” she relates.

It’s the pause and the stretch that are thrilling to the artist. “Just as the dancer defies gravity, art is about the power of an impulse to defy the rules,” Liotta explains. “Art that really speaks to me is that traditional reach for something transformative. Like dance, it shouldn’t sit there. You want to catch something airborne.”

Catching something airborne is a fitting way to describe Liotta’s oeuvre. She starts with inanimate material: marble, stone or slate. Once she’s shattered the stones for a sculpture, she ties them with cord and hangs them from pieces of hardware. When she lets the stones fall free—suspended from the overhead structure—they gracefully move within their space. As the artist would say, they begin to dance.

While Liotta is experienced at carving stone, she prefers hauling chunks or slabs of rock to the alley outside her Northwest DC garage-cum-art studio, where she takes a sledgehammer to them to create smaller, imperfect shapes with jagged edges that expose the energy within.

“I look at each piece of stone almost figuratively. I see them as figures and I want them to have a vibrato—like when you play a string instrument, the string vibrates.” she explains. “I want them to breathe. They’re not stiff—they move.”

Liotta sources stone from Tri-State Stone in Bethesda and works with Fernando’s Marble Shop in Rockville to select granite, marble and quartzite. She chooses specimens not only for color and depth but also for their density, translucence, size, shape and what she calls “activity—how the veins move and interact.” As the artist observes, “It’s about finding the right stone to sing in a particular space.”

Commissions are collaborative efforts between Liotta and her client—often an architect or interior designer. First, they visit the space where the artwork will hang, discussing different ideas and locations. Liotta often finds inspiration on site. “There’s a lot of just sitting there, experiencing where the ceiling is, the height of the space, where the walls are, where the life of the room is—and just trying to understand where the energy moves,” she reveals.

Liotta takes photos of the space, prints them and draws her ideas directly on the prints. Then she shares these concepts with her clients and discussions ensue. Clients also help choose stone for each piece. For one commission, Liotta was asked to source rock from a lake in Michigan where the client grew up; another client who taught Classics hired her to create a sculpture using Greek marble.

Born in Cleveland to “art-conscious” parents involved in music and visual arts, Liotta studied fine art and dance at Sarah Lawrence College, where one of her mentors was the renowned dance instructor Bessie Shönberg. “What Bessie taught me in choreography class informs what I do more than anything else I ever learned,” Liotta avows, “from how to look at art to how to have a discerning eye and how to clear out extraneous work.”

Liotta painted throughout college. Eventually, she moved to Washington and dedicated herself to pursuing art full-time 35 years ago. Her early work explored large-scale paintings on unprimed canvas, which she ripped, gathered and hung. However, she wanted more dimensionality than what canvas would allow. “I wanted to make my lines and trajectories out in the air,” she recalls. “I wanted them to soar in three-dimensional space—and I just fell in love with stone.” She began working with large boulders and river rock, then moved on to more delicate, shattered stone and suspended chunks of rock.

Liotta accepts private and public commissions. A large-scale sculpture is on permanent display at Legacy Memorial Park in Washington, DC. The Phillips Collection owns one of her pieces, and her work is shown internationally with the Arts in Embassies program and privately around the United States.

“I see my work as akin to chamber music,” Liotta observes. “There’s a certain austerity—the minimum of elements that weave, blend and soar until they achieve eloquence.”

Phillips Collection Intersections: Icarus

In this video, artist Barbara Liotta installs Icarus in the Main Gallery at The Phillips Collection. Icarus, Barbara Liotta October 22, 2009-January 31, 2010 Conceived as a portrait of human energy and inner strength and as a symbol of flight and aspiration, this large-scale sculpture is made of strings and stones and suspended from the ceiling.

A performance in partnership with the Washingon Ballet. Andile Ndlovu of the Washington Ballet responds in dance to Barbara Liotta's sculpture, Icarus, and Maurice Ravel's Sonata for Violin and Cello performed by Yvonne Lam and Ignacio Alcover. Ndlovu and collaborator Septime Webre, artistic director of the Washington Ballet, use the abstract forms of the artwork and the mythical character's backstory as inspiration.

Barbara Featured In "100 Top Creatives"

Mark S Price, Sculpture Magazine Review

Six of Barbara Josephs Liotta’s seven recent granite-shard installations at Reyes + Davis featured titles referring to the Pleiades, the seven daughters of Electra and a cluster of stars in the Taurus constellation. With the exception of a seventh (much larger and more horizontal) rock cluster (Poseidon Project Part I), each installation hung at roughly the same horizontal distance from one of the gallery’s two longer walls and occupied an imaginary vertical shaft from ceiling to floor above its invisible footprint of about 10 inches. Because the Pleiades differentiated themselves one from the next only subtly and were separated by repeated intervals, serial form overshadowed content, and any hint of narrative or drama resided within each cluster rather than between them. Aligning the configurations close to the walls subverted their in-the-round identities while playfully transforming the entire installation into a kind of air-infused relief sculpture.

The essentially monochromatic range of each work tells us that, for Liotta, color is secondary. At least one strong light source threw elegantly nuanced shadows from each Pleiade onto adjacent walls or floors. The tonal subtleties surpassed the color relationships in drama and interest. Liotta employs competing archetypes. Broken-off pieces of already polished granite entangle the Promethean reach of man with the hand of a creator-god. Or each pebble on a string could be David’s missile about to be slung at Goliath. They are as likely to be a lapidarian’s raw materials as weapons in a children’s rock-throwing fight.

Poseidon Project Part I, Liotta’s final piece at Reyes + Davis, required its own room to contain a footprint of six by eight feet. Viewers were able to walk around and even through portions of the piece. A tiny child could have tottered about underneath it without ever touching a stone.

The Phillips Collection hosted the most soaring accomplishment of Liotta’s two-part show as part of its Intersections series of contemporary artists. Icarus is a symmetrical, ascending parabola whose smallish rock pairs insinuate a spinal column. Two implied curving planes extend from the spine as wing-like extrusions, formed by Venetian blind cords. The mythical character occupied fully half of its room and invoked Christ’s Descent from the Cross, a magnificent insect in mid- flight, as well as the doomed Icarus. While the vertically inert Pleaides playfully posed questions of existential scale and time, Icarus provided an anti-gravitational counterpoint by dwarfing nature’s power in favor of flawed humanity.

Collector Mera Rubell makes rounds of Washington's isolated artists

You could call it a Hanukkah miracle. Or the arrival of intelligent life from another planet. Last Saturday at 5 a.m., while the rest of us slept, megacollector Mera Rubell walked among us, hunting local art.

The Miami-based maker of artists' fortunes has, with her husband, Don, put a dozen Leipzig-based painters on the international art map. Together the couple bought some of the earliest Jeff Koonses. Their collection includes works by Takashi Murakami, Keith Haring and Kara Walker. Mera Rubell, 66, has access to art stars stratospherically more successful than anyone working in Washington.

And yet, here she was. She'd bolted into Washington for an art marathon, visiting 36 artist studios in 36 hours. Straight.

It was Mera's idea. (We must call her that. She'd insist.) She did it for the Washington Project for the Arts, the city's beleaguered but still humming arts group. She offered to pick 12 artists whose works would be among those that would hang in "Cream" a WPA benefit auction exhibition opening at American University's Katzen Arts Center on Jan. 30. A lottery system determined the 36 studio stops.

From her first appointment on Saturday at 5 a.m. in Southwest to her final Gaithersburg rendezvous at 3:30 p.m. on Sunday, Mera chatted, questioned, prodded, hugged, gesticulated and even adjusted one artist's errant scarf during studio visits of exactly 30 minutes each.

How did she do it? Efficiently. WPA Executive Director Lisa Gold traveled alongside and held Mera to a tight schedule. Her chariot? A white Mercury Grand Marquis belonging to independent taxi driver Bunchar Panich. Mera hired him from the taxi stand outside her hotel. He shuttled her and her small posse for all 36 hours, resting when Mera rested, in a hotel room she booked for him.

(Yes, she scheduled snacks and two naps back at her home away from home, the hip, low-budget Capitol Skyline Hotel near Nationals Park that her hotelier family owns. But does a break from 2:15 a.m. to 5:30 a.m. really count as rest?)

At each studio Mera was all warmth and encouraging words -- even as she told artists that they weren't working hard enough. Or when she asked if there was more to their practice when she clearly hoped there was. To put her hosts at ease, she asked about partners and kids.

"There's a wealth of amazing talent in this area," she gushed after 12 hours of touring. She has found work she was excited about, artists she wanted to know better, artists who turned her on.

Yet by the end of her trip, Mera came away with some stark impressions, impressions Washington art insiders already know but are loath to discuss.

Like: "There's nothing to fight for here. There's not enough contemporary art being shown."

And: "As an artist, you're not going to make any money. A few nice words from [this critic] -- that's all you can get."

And: "There are so many desperate situations here. It's scary."

Mera's troll through Washington's art warrens was akin to Santa visiting the Island of Misfit Toys. Below, a snapshot of her odyssey.

Sunday, 8:30 a.m.:

Harrison Street NW

After huddling in Barbara Liotta's studio examining rock sculptures suspended from the ceiling, the group is back inside Liotta's living room. This is Mera's fifth studio since 5:30 a.m.

Liotta offers coffee and food. Gold gives the okay -- the group is ahead of schedule.

"There are artists who feel extremely isolated here," Mera ventures between bites of frittata. "I've never seen such isolation and loneliness." She asks Liotta who she talks to about her work.

Liotta pauses. Her answer: No one. Not other artists. Not her dealer.

Why not?

"It's some combination of not trusting it and not . . . " Liotta trails off. "I haven't a clue."

"If you were living in New York, you'd be pushing your work a lot harder," Mera says with firmness. "With all of the millions of dollars poured into museums here, why are artists so contained?"

A few minutes later, taking cover under Liotta's doorway before venturing into the cold rain, Mera considers the peculiar situation that is the Washington art world.

"The pecking order is so vague here, so nebulous," the collector says. In New York, top artists become untouchable. For them, it's a badge of achievement to pull up younger ones, to mentor them. Not so in Washington, where no one knows who's on top and everyone is on the defensive.

"It's like children fighting for their parents' attention," Mera say. "It's basic competitive survival here -- you don't give an inch."

There's a reason artists move to New York.

ART: Contemporary artists inspired by the past

Eager to inject contemporary art into the Phillips Collection, museum director Dorothy Kosinski has launched an appealing enterprise to integrate new and old works within the galleries.

Called "Intersections," the series invites contemporary artists to create pieces based on their reactions to treasures from the Phillips' holdings. Ms. Kosinski views the effort as extending founder Duncan Phillips' vision of the museum as both "an experiment station" and intimate place for considering the formal relationships among artworks.

"Duncan Phillips left a mandate to continue a vibrant dialogue with our time," she said during the opening of the series earlier this month.

The first installment of "Intersections" is a promising start to renewing this idea. It places contemporary art — a video, a sculpture and wall reliefs — within the older spaces of the museum rather than a separate gallery so they blend into the collection.

The juxtaposition encourages a fresh view of familiar 19th- and 20th-century paintings as seen through the eyes of three female artists: New Yorker Jennifer Wen Ma, Washingtonian Barbara Liotta and Rhode Island-based Tayo Heuser.

The trio was chosen by Vesela Sretenovic, the Phillips' curator of modern and contemporary art, who has tapped four more women to intersect with the collection in the future.

Not to be missed in a nearby gallery is Ms. Liotta's floor-to-ceiling sculpture rising in a corner of the space. Titled "Icarus," her suspended installation is named for the Greek mythological character who flew too close to the sun and fell into the sea.

Its wings are made of synthetic black cords with small rocks suspended from a central ridge of hanging fringe. This graceful arrangement of stones and strings creates an intriguing study of gravity and figural allusions.

So how does this installation relate to the five seemingly unrelated paintings in the room? The obvious answer seems to be the Argentine granite of the rough stones, which matches the rusty tones of the paintings and reddish color of the wooden gallery floor.

Ms. Liotta replies by comparing her sculpture to the character studies shown next to the piece, including paintings of a woman by Chaim Soutine and a painter at his easel by Honore Daumier.

She conceived "Icarus" as representing "the strong will to rise and soar," an ambition similarly expressed in the paintings, rather than a literal portrait of the Greek figure.

Her stone-bound installation also might be seen as the visual embodiment of a human spine and a stringed instrument, as expressed by the fiddler in Eugene Delacroix's "Paganini," which also hangs in the gallery.

Even without the paintings for comparisons, Ms. Liotta's sculpture succeeds in enlivening the space with the dynamism of a stretching dancer. Its power stems from the tension between the heavy stones and delicate webs, and the tightly controlled configuration of the piece.

Claire Huschle in Sculpture Magazine

…Barbara Josephs Liotta’s Terrace Descent also examined the shared vocabulary of sculpture and architecture. Over a corner facing the stairs, Liotta used cord to suspend chunks of black marble and granite from a series of parallel metal rods. As the rods receded into the corner, the marble and granite pieces likewise seemed to recede, resulting in an inverted “marble staircase.” Like Davis’s piece, Liotta’s work removed all sense of functionality. And like Luttwak, Liotta called up notions of quarries and earth movers. But Liotta’s work also exploited the architecture of the space by incorporating motion. As the wind swept down the stairs, Terrace Descent shifted and twisted, despite it s apparent weight. The work combined the kinetic experience of sculpture with the environmental experience of the space itself.

Art That Rocks (The Washington Post)

Liotta’s minimalist sculptures are made from rocks she finds in riverbeds or on the seashore and then binds with cords or chains.

There is something strange, severe and dynamic about these stones in bondage. That power derives from the tension between the materials and the use to which Liotta puts them. The stones are inherently beautiful, shaped and smoothed since time immemorial by the forces of nature. But those qualities take on different meanings when the stones are placed in tightly controlled context as part of an artwork. Instead of nature as a free-flowing force, it becomes captive, forced to play a role in art.

Seeing a cluster of rocks bound with black cord and hanging in midair, suspended from a chrome chain, calls to mind all manner of images. Up close, it looks like a riverbed, hovering above ground. From a distance, the same piece can seem ominous, like a person dangling in the air, or utterly benign, like a weird Stone Age wind chime.

Those associations vary from one work to the next, depending on the shape, size, color and type of the stones, such as slate or granite, and the way Liotta employs them. But all of them have a psychological presence. Its an impressive body of work.